Interviews

A Chat with Frontiers Speaker, Greg Sawyer

September 26, 2023

Frontiers in Nanotechnology speaker Greg Sawyer gave us a preview of his upcoming seminar and took us on a journey through the revolutionary world of advanced microscopy techniques.

Q) Welcome our inaugural speaker for this year’s IIN Frontiers in Nanotechnology seminar series, Greg Sawyer. Gregory is the chief bioengineering officer at the Moffitt Cancer Center and also the chair of the Department of Bioengineering at Moffitt.

GS) It’s a pleasure to have an opportunity to spend time with you.

Q) The title of your upcoming lecture is “Life in Miniature: Immuno-Oncology in Three-Dimensions.” How would you describe that to say, a sixth grader?

GS) I would tell them that each of you is unique. And when we’re trying to develop treatments, we need to try to find ways to treat you. So, one of the things we’re doing in engineering is making miniature copies of your important parts, thousands of pieces and parts, so that we can study treatment options. Our immune systems try to keep us healthy, and we’re trying to engage our immune systems to fight terrible diseases like cancer.

Q) Tell us about your journey to the Moffitt Cancer Center.

QS) It was terrible. I worked at NASA in the early nineties on the Mars Rover. I didn’t get involved in cancer research until I was a cancer patient. In 2013, I was diagnosed with stage 4 metastatic cancer. It was a total surprise diagnosis; I was a healthy person otherwise. And I started looking for ways that engineers could help in cancer research. Ten years later, I’ve taken that approach and those tools to a cancer center, which is the Moffitt Cancer Center. And we’re starting a department of engineers inside of a cancer center. So we’re embedding it within the center.

Q) Few people could make that sort of career pivot. Was it more challenging than you had originally expected?

GS) I’ve been focusing on this for so long. And both professionally and personally, I’ve had nothing but support. There’s a caveat, though. In 2013, my particular diagnosis did not have a 10-year survival curve. It was a cancer measured in a finite number of Christmases. Right? So, if this was important to me, everybody, from my university to my family, even my colleagues in the research fields that I was in, all supported it.

Now, I’ve been doing it for ten years. In the beginning, I said cancer would be the last problem I worked on. And that’s an easier statement to say when you are looking at a finite amount of time. You go out ten years; this has been exhausting and remains challenging daily. You’re trying to learn more and more about cancer biology as you’re trying to stay up to speed with new therapies, working closely with medicinal chemists and pharmacology. It’s like drinking from the fire hose every day.

Q) How many people are you working with right now at Moffitt?

GS) It’s probably over 50; we try to be an integration platform. And our goal is to be obsolete, to solve all the problems to be obsolete. But similarly, our goal is to provide so much access to these microtissues, to life in miniature, that we aren’t needed to help run the test track. Everybody can do that on their own. And then, we can go find what’s holding up progress and apply our engineering efforts there. We felt the first thing biology needed from the engineers was access to realistic tissues in the laboratory.

Q) What’s the atmosphere like working with such a large and talented group?

GS) We’re a very collaborative group. We derive some of our own energy from the infectious enthusiasm that we see from others when they see things that they’ve been working on for a lifetime for the first time in a lab. Imagine you’ve been treating patients and never seen a mean cell kill a cancer cell. We’ve had researchers almost cry. Just go, “holy cow, I can’t believe I can see this.”

Q) What is the biggest challenge you’re running into in micro-speed techniques and their impact on immuno-oncology?

GS) On the low level, it is simply being gentle enough to observe the desired phenomena without destroying your experiment. You can look with great resolution, but that comes with great intensity, which causes a lot of damage to the very thing you’re trying to study. Being able to see deep into tissues and being able to do that for prolonged periods of time has been a major obstacle to the field.

Q) On the flip side, what are you working on right now that you’re most excited about?

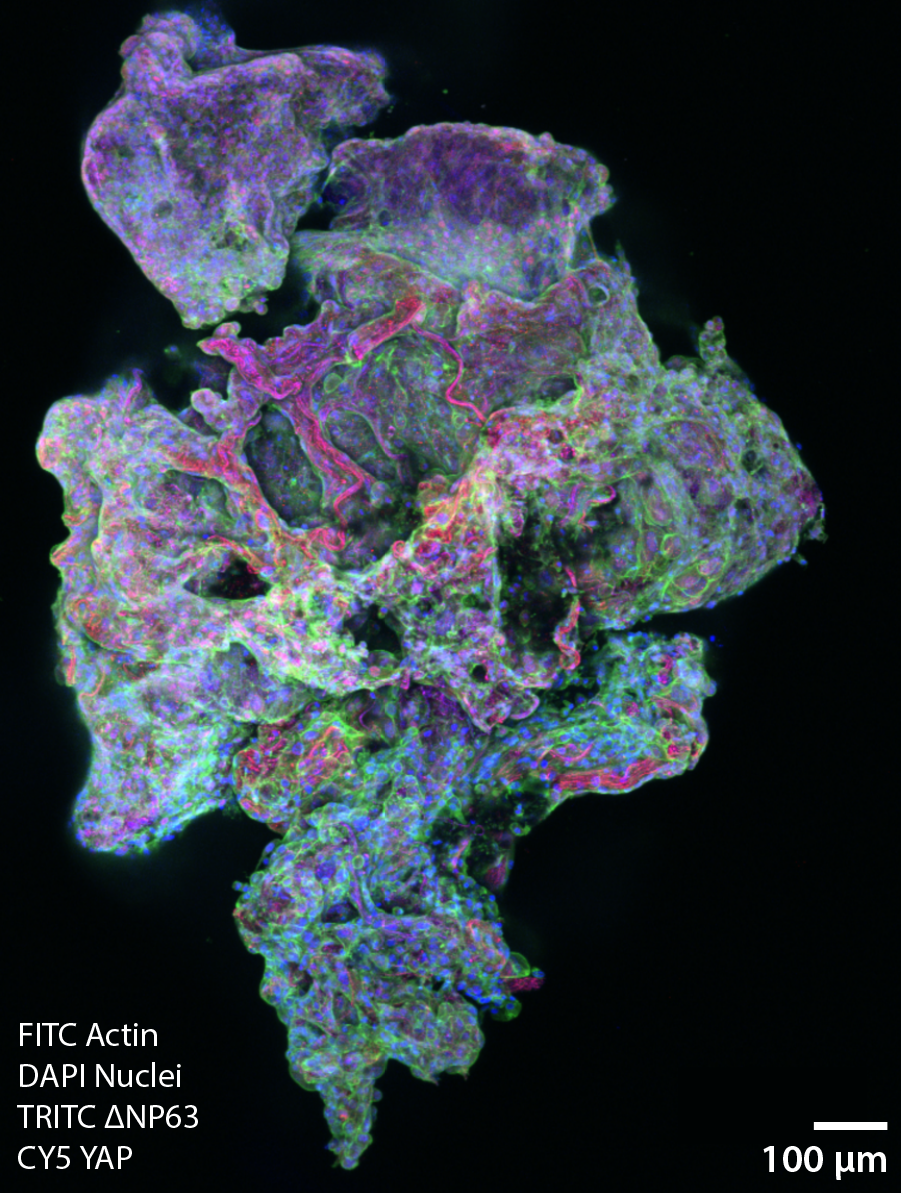

GS) For us, every year, every week, every day, we’re pushing to increase complexity in a precise way. Meaning that, on the one hand, with microtissues, each one is unique. We have the complexity, but a lot of times we don’t know what we have. It isn’t fully defined. So we have a tissue but don’t know everything about it. Then, on the other hand, you say, well, if you could build a microtissue from scratch bespoke, you design it. How would you do that? So, analogous to material scientists developing materials one atom at a time, we’re trying to develop microtissues, one cell type at a time. So, things that can be a little bit more precise and complex, where we know all the constituents.

We improve every six months. But we’re still a long way to go from having real patient-like complexity.

Q) Have there been any moments where you’ve gone, “This is was not the direction I thought we were going to be heading, and we have to go back and start from scratch?”

GS) Every day. If ever you want an opportunity to be humbled, try to manipulate biology. It’s a system that’s had 500 million years of tinkering. And as you poke, manipulate, and try to control, you’re arguably pushing against 500 million years of experience. So yeah, every day. Every day, something happens where I think, “Well, that was in the wrong direction.”

In terms of an engineering mistake that we pivoted on, it was 3D printing. We tried to 3D print tissues for years, made some progress, and then felt we had to make changes. And now, eight years later, we’re back to thinking about, “maybe there is a merit in doing a little 3D printing.” These things are cyclical. This is what engineers do. We live on a test track. And we’re gonna we’re gonna break things every day. The whole benefit of life and miniatures is we break things in the safety that we’re not breaking you.

Q) That’s an interesting way to put it because I’ve worked with so many frustratingly humble scientists.

GS) That humility comes from the field. You asked how many times things go wrong. It’s every day! And the word itself, I hate. When people ask us “what we do [when something fails],” we say we search again. That’s the nature of our word. To repeat and to search again. So we’re exhausted.

The people I admire most are just these gracious scientists who have had opportunities to make discoveries that can stay at it for the long term because that’s an act of endurance. Most days, you go home and don’t say, “Oh, man, today was great. Everything in the lab worked perfectly.” It’s usually more like “We’re gonna redo that day tomorrow. It didn’t count; we’re gonna redo it.”

Q) Do you ever check back in on the Mars Rover?

GS) No, it was never about the machine. It was about the people. And that group is a different group now. In 1992, I can pretty much remember every person’s face and name. But we’ve all now gone into other areas.

Q) How do you relax at the end of the day? What do you do when you need to get out of the lab and clear your head?

GS) It’s basically anything physical: running, the gym. What happens is there’s a different type of exhaustion. There’s mental exhaustion from tackling unsolvable problems that require a mental fortitude that some people have much better than me. Sometimes, the only way to get past mental exhaustion is to go find physical exhaustion and force your mind to work on something more, focused on yourself. At least for me, I find those things are probably the best way to do resets.

Outside of that, I don’t do as many creative things as I used to do. I was enamored with art. I now find myself more of an observer and an enthusiast of other’s art and less of it on my own. I enjoyed drawing, woodworking, taking ideas in my mind, and getting them down on paper. Those things have become less of an outlet for me. I often have to do those things when I have to illustrate my concepts, so it starts feeling a little more like work.

And then with the family, it’s always your children’s hobbies. For me, it’s automobiles, it’s welding and sculpture, whatever they like doing.

Q) Your children are now 18 and 22 and seem to follow in your footsteps.

GS) One is a freshman in college in my old department, and the other one’s starting his graduate career in my lab. I was a professor, and if you talk to any professor, they’ll tell you that their kids grew up in the lab. When you’re a professor, you have two families. You’ve got an academic family and a personal family and friends. You have two networks. And at least for me, those two networks overlapped, and my kids grew up in a lab. So having him, who’s been in that lab, knows what we do. Oh, my God, it’s a dream. It’s like, “Give me 10 of these!’

Q) My six-year-old has been telling people that I am a scientist, and I know one day he will figure out that my job isn’t in the lab but in writing about the work of other scientists.

GS) When JFK toured one of the NASA facilities, I think he ran into one of the janitors and asked, “What you do here?” And the janitor says, “I help launch rockets.” We all have our part. And JFK was so struck by that he repeated that story often. I certainly heard about it.

Q) What do you think about the IIN’s research?

GS) So, first off, Northwestern’s amazing. You’ve got a tremendous presence up there. Bridging the physical sciences with cancer. Everything from your material sciences to your nanomaterials, your mechanical engineers, and your chemists, all integrating together around cancer. Plus, you have a great cancer center. In many ways, Northwestern’s doing it; you guys have this intersection and an ecosystem of engineers and the physical sciences working in cancer. So it’s a pleasure for me to come up and see it.

Q) How can people keep track of what you’re working on and stay updated with Moffitt and Sawyer news?

GS) Just stay tuned. We’re not hard to find. We have our website moffitt.org/newsroom, and our Twitter account @MoffittNews. I don’t have Facebook. I don’t personally have anything. But anyone can reach out to us and get involved.